Fast and Unsteady

The top funds don't plod along; they kill often

To succeed long-term you’ve got to excel short-term. Slow and steady isn’t going to cut it. Those conclusions don’t come easy to me. I’d much prefer the latter to the former—steadfastness over streakiness. But the data is hard to deny.

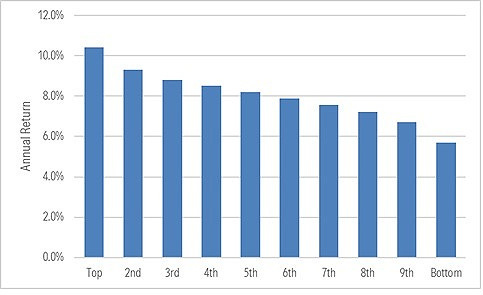

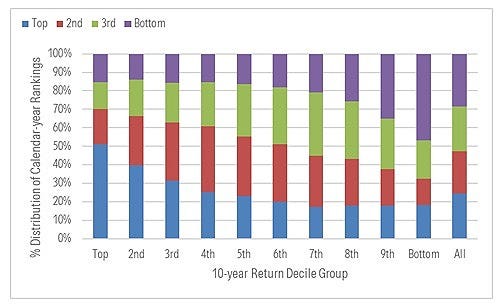

The data: I compiled the 10-year annual returns (as of Dec. 31, 2025) of more than 9,000 U.S. stock, international stock, and taxable bond funds. I then sorted those funds into deciles based on their 10-year annual returns vs. category peers. The highest-returning funds were in the top decile, the lowest in the bottom, and so forth.

From there, what I wanted to know was how each decile’s short-term performance compared. For instance, did top-decile funds have pedestrian returns in most calendar years punctuated by one or two massive years that vaulted them ahead over the full decade? Conversely, did cellar-dwellers notch standout returns in just as many calendar years as top funds but undo themselves with a few horrid years? Etc.

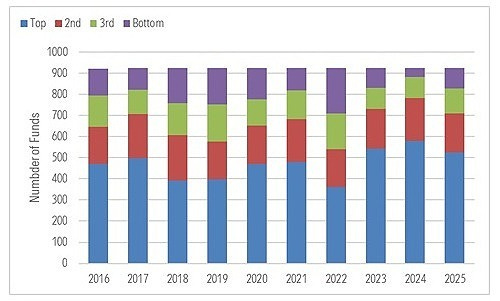

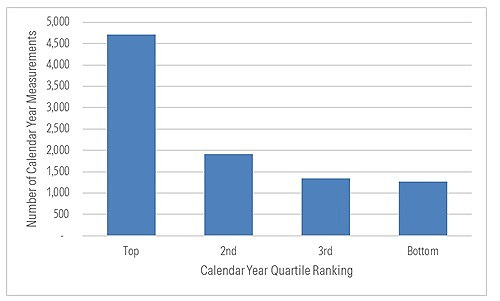

So what I did was pull each fund’s calendar-year returns for the 10 years that made up the decade — 2016 to 2025. Then I sorted funds into quartiles based on their returns in a given calendar year compared to their category peers.

For instance, there were 926 funds whose trailing 10-year returns ranked in the top decile of their category as of Dec. 31, 2025. I ranked each of those 926 funds against other funds in their category based on their return as of Dec. 31 of each calendar year. Here’s what that distribution looked like.

All told, the top funds over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2025 ranked in their Morningstar Category’s top quartile in a given calendar year about half the time. In other words, it wasn’t uncommon for the long-term winners to be short-term victors or, put another way, it was atypical for these funds to muddle along and then, bang, have a huge, decade-making year. They got it done long term because they won often over these shorter, unpredictable intervals.

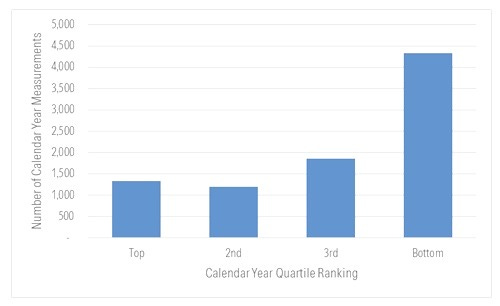

How about the other end of the spectrum — the worst performers over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2025? Here’s the same breakdown of calendar-year ranks for that bottom-decile group.

In all, the worst-performing funds over the decade ended Dec. 31, 2025 finished in the top-quartile of funds in their Morningstar Category in a given calendar year only about 15% of the time whereas they landed in the bottom-quartile nearly half the time. That’s more or less the inverse of what we saw for the top-decile funds.

That covers the distribution of calendar-year ranks for the best and worst funds over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2025. Now here’s the full picture, encompassing all 10 of the decile groups.

As you move from the best performing funds (on the left) toward the worst performers (right), the share of top-quartile calendar-year ranks shrinks while third- and fourth-quartile finishes swell. It seems only to reinforce the reality that the funds that with the best performance over the decade ended Dec. 31, 2025 excelled most often over these shorter periods and the opposite for funds that underperformed.

Slow-and-Steady (and-Mediocre)?

It’s also striking how second-quartile calendar-year ranks didn’t seem to correlate with long-term outperformance. Indeed, it was the fifth and sixth decile groupings—i.e., the middle-of-the-pack performers—that had the largest share of second-quartile calendar-year showings. This suggests slow-and-steady led to largely mediocre results.

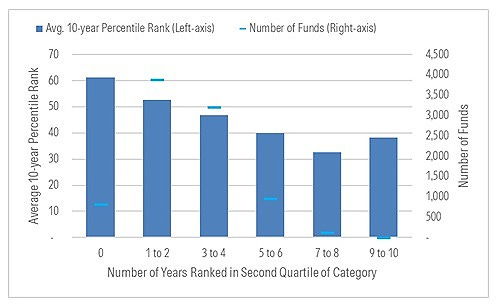

There also simply aren’t that many funds that would fit the definition of “slow-and-steady” to begin with. Consider that the average fund that started and finished the full 10-year period ranked in its category’s second-quartile in only around one-quarter (2.6) of the 10 calendar years.

It’s true that the more often funds landed in the second-quartile in the calendar years, the better their long-term returns tended to be, as shown below. But there just weren’t that many funds like that — only 144 finished seven or more calendar years in the second quartile.

Unfortunately, you’ve got to be better than good short-term to be among the best long term. Fast and unsteady rules.

The upshot: Given how utterly unpredictable these shorter intervals are, and how pivotal they appear to be to longer-term elite performance, it’s a fool’s errand to try to handicap which funds will rank near the very top of their peer group 10 years hence. Stick with what you can count on—such as the persistence of fee differences between funds—and that should yield a more-than-acceptable result.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of Jeffrey Ptak and do not necessarily reflect those of Morningstar Research Services or its affiliates.

This is such a powerfull analysis! The data on top-decile funds landing in top quartile 50% of the time really challanges the whole slow-and-steady narrative. I always assumed consistency meant avoiding big swings but your breakdown proves winners need to kill it regulary. The chart showing middle performers had the most 2nd quartile finishes was eye-opening, basicaly proving mediocre is the new steady. This changes how i think about fund selection completly