We Are Automatic

Parsing Vanguard's terrific "How America Saves" Study

Vanguard just released its annual “How America Saves” study of the U.S. retirement plan market. It’s terrific, offering a broad and compelling synopsis of key trends and statistics across the “more than 1,400 qualified plans and nearly 5 million participants for which (it) directly provides recordkeeping services.” You read it and you feel like you have a decent sense of what is going on in 401(k) plans writ large.

At first blush I don’t see a lot of big changes from last year’s study to this year’s installment. Nevertheless, the findings underscore the extent to which retirement plan investing has been mechanized. People get auto-enrolled, auto-escalated, auto-company-contribution-matched, auto-asset-allocated, auto-rebalanced, and auto-glide-pathed. And you know what? It seems like they’re better for it.

In this post, I’ll cover some of the biggest things that jumped out to me in reading the study.

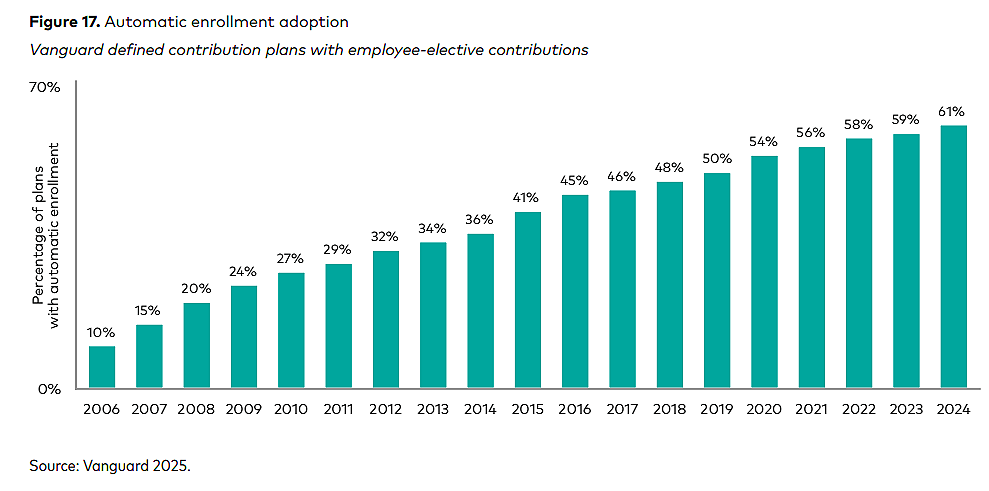

Nearly Two of Three Plans Auto-Enroll Participants

This percentage has ticked up one or two percentage points each year of the past decade. It is now nearly twice as likely as not that when you start work you’re auto-enrolled into your firm’s retirement plan. That’s great.

Auto-Enrollment Boosts Participation

Why is it great? Even when you control for a bunch of variables, like Vanguard did, you find that participation rates are significantly higher among plans that auto-enroll participants than those that don’t. And who does it seem to benefit the most? Lower income workers; younger workers; less tenured workers.

All told, 94% of employees eligible to participate in plans featuring automatic enrollment do so. That is significantly higher than the 64% participation rate in plans that don’t feature auto-enroll. We need more people saving, especially in some of the more vulnerable cohorts I’ve highlighted. It’s very encouraging to see it happening.

People Are Saving More (Without Necessarily Even Trying)

Auto-enrollment is one thing. But then there’s the matter of whether the contributions being made are sufficient or not. There’s “saving” and then there’s “saving”.

Fortunately, it appears technology is helping participants get over that hump, too. I’m referring to auto-escalation, whereby the plan automatically ratchets the contribution rate (as a percentage of eligible pre-tax income) higher on a predetermined schedule. Before we get to auto-escalation, it’s important to get a sense of what the baseline contribution rate is among participants who are auto-enrolled. Here is that.

What you find is that nearly all plans auto-enroll their participants at 3% or more but the percentage that auto-enroll at 5% or more has been rising. A decade ago, only 27% of plans auto-enrolled participants at a 5% contribution rate or higher. Now nearly half of plans do so.

That’s the baseline. Here is the trend in auto-escalation rates:

We haven’t seen dramatic changes - it appears that two-thirds of plans with auto-enrollment auto-escalate at 1% per year, which is similar to where it’s been over the past decade. However, it’s becoming more common for plans with auto-enroll to offer this feature. Moreover, they’re lifting the caps on increases from 6% - 9% of eligible pre-tax income, which was more common a decade ago, to 10% - 20%.

The report also shows that merely offering auto-enrollment is more likely to induce participants to elect auto-escalation as well. You can see that from the stats on plans that don’t have auto-enroll but offer an auto-escalation feature. 41% of these plans offer the feature, which is available to 75% of those plans’ aggregate participants. But only one-third of the participants offered auto-escalation opted for it.

It appears the percentage of eligible employees in these plans opting for auto-escalation has been falling, not rising. For instance, a decade ago only 55% of participants in participating plans offered the feature, with nearly half (24%) of the participants electing to use it.

So auto-enrollment appears to have multiple virtuous effects, getting people into plans, getting them started on saving, and ratcheting the savings rate gradually higher.

Then There’s the Match

As we know, one of the other benefits savers confer from participating in their plan is capitalizing on the employer match. Did plan design—auto-enrollment vs. voluntary election—show up when Vanguard looked at deferral rates inclusive of the employer match? It did.

The overall deferral rate, including the employer’s matching contribution, was 12.5% for plans featuring auto-enrollment, which was nearly 1.5% higher than the rate in plans that didn’t offer it. This tended to hold even when Vanguard controlled for various other attributes like income level, age, gender, tenure, and account balance.

Could there be some conflating factors that explain why the deferral rate was higher for plans that offered auto-enroll? Yes, as you tend to find that larger firms, which are presumably in a better position to offer a matching contribution, are more common among plans that offer auto-enroll whereas smaller firms with less wherewithal to contribute alongside their employee participants make up a bigger chunk of plans that don’t offer auto-enroll.

That Money Is Pouring Into Set-It-and-Forget Portfolios

Where is all of that money going? Nearly all of the contributions in auto-enroll plans are pouring into target-date funds. Those strategies—which feature a preset asset allocation, rebalance regularly, and gradually adjust the asset mix as the investor nears retirement, obviating the need for them to tinker—are the default 98% of the time.

You can see it pretty starkly in this chart, which shows the number of investment options participants actually choose compared to the number they’re offered. When you strip out multiple target-date funds and treat them as a single fund, you find the average plan offered nearly 18 different investment choices in 2024. But the average participant used just two funds, one of those very likely being a target-date fund.

Vanguard estimates that as of 2024 two-thirds of all participants was outsourcing asset allocation and investment selection to the firm. They might still choose a particular target-date fund (though that’s becoming less common with auto-enroll and defaulting) but Vanguard is taking it from there. That represents a nearly 20 percentage-point jump from a decade ago, when less than half of participants were opting for a target-date/risk fund or participating in a managed account program.

This has predictably translated to much lower trading activity, with only 1% of target-date fund participants transacting in 2024, compared to 3% of target-risk fund investors and 11% of all other investors.

Investors are largely being auto-enrolled into a target-date fund, the investment management is taken care of for them, eliminating the need for them to take further action beyond regularly contributing. So the question becomes: How have these funds done?

Set-It-and-Forget-It Has Worked for Investors

Vanguard plotted out the risk and return characteristics of different types of retirement plan investment options over the five years ended Dec. 31, 2024. What you find is that the risk/return target-date fund investors experienced was explained almost entirely by their age, which will tend to be inversely related to how much equity exposure they have through the target-date fund. It’s almost a perfect line.

(Sorry the image is hard to read. I needed to screencap all four plots, though.)

What you find as you range away from target-date funds is a wider dispersion of outcomes based on age range, some of that by design (i.e., managed accounts), but also by idiosyncrasy (i.e., participant taking on too much or little risk; investment option performing less predictably; etc.)

I’m near my substack limit so here’s the money chart. Because they weren’t jumpy and simply stuck with it, participants in Vanguard’s target-date funds earned all of those funds’ total returns. The retirement system is far from perfect, but that’s awesome to see.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of Jeffrey Ptak and do not necessarily reflect those of Morningstar Research Services or its affiliates.